As School Choice Tax Credit Goes National, the Battle over Regulation Begins

States can now sign up for the new federal tax credit for private school choice, which could potentially spread voucher-like programs nationwide. But the public still wants a say in how the government regulates the new policy — and how much. Supporters want the program to be uncomplicated, both for nonprofits granting scholarships and the […]

States can now sign up for the new federal tax credit for private school choice, which could potentially spread voucher-like programs nationwide. But the public still wants a say in how the government regulates the new policy — and how much.

Supporters want the program to be uncomplicated, both for nonprofits granting scholarships and the private schools participating. Others want to ensure that students who remain in public schools can benefit from the program, while critics oppose the basic concept — a dollar-for-dollar tax credit for those who donate up to $1,700 annually to a scholarship-granting organization.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

They want the Trump administration to focus instead on supporting public schools.

“The federal government should invest in strong, inclusive, well-resourced public schools — not incentives that drain support and weaken safeguards,” one Tennessee man wrote in a letter to the Treasury Department and the IRS, among the more than 2,100 comments on the new law submitted by the Dec. 26 deadline.

With the tax credit already on the books, the Federal Scholarship Tax Credit Coalition, which represents more than 200 school choice advocates, private schools and scholarship organizations, wants the administration to keep the program simple.

The organization wants officials to make it “as easy as possible” for scholarship-granting organizations to participate, for taxpayers to contribute and to “maximize” the number of students who will benefit.

Their letter calls for the administration to clear up some potential confusion.They want officials, for example, to keep recordkeeping requirements for participating nonprofits from being “overly burdensome or onerous.”

John Schilling, a consultant who lobbied in favor of the program, said he hopes Treasury officials will release rules by summer.

‘Very well prepared’

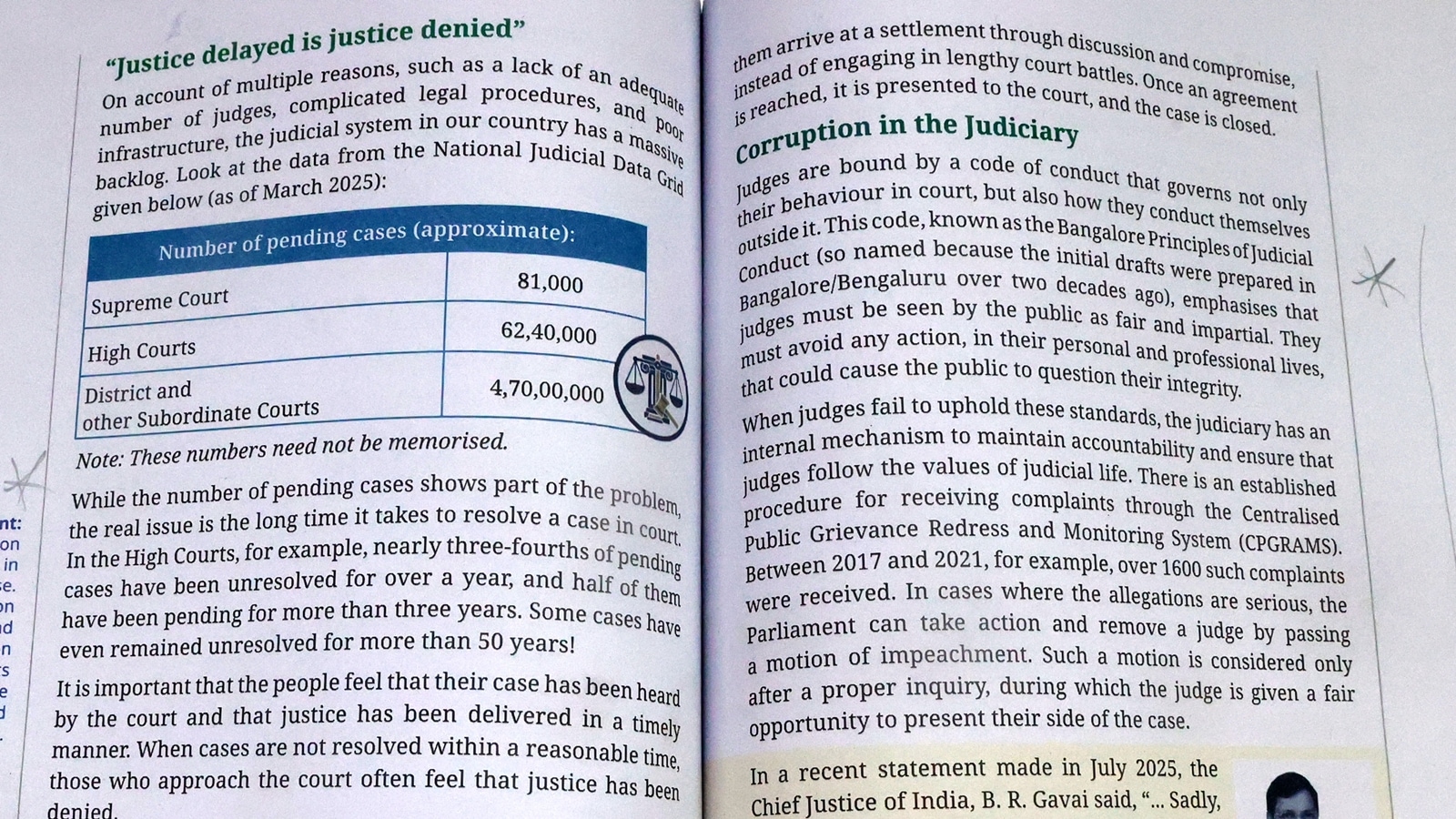

President Donald Trump signed the new program into law in July as part of a large tax cut and spending package. Because it’s hard to predict how many taxpayers will donate and claim the credit, it’s not yet clear how much the program will cost the government. Kristin Blagg, a principal research associate at the Urban Institute, a left-leaning think tank, estimates that after an initial “ramp-up period,” the program could generate between $2.7 billion to $6.1 billion annually.

Scholarship groups could begin awarding funds to students in early 2027, but it might take until that fall for them to raise enough money.

“The ones that are serious about doing this are going to be very well prepared,” Schilling said. “I’m hopeful that they will line up a lot of donors who will give in the first quarter of 2027.”

So far, the governors of Colorado, Iowa, Louisiana, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee and Texas have said they intend to opt in, while those in New Mexico, Oregon and Wisconsin have announced that they won’t. But Schilling said he thinks that’s a mistake because donors could just send their money to a scholarship organization in another state.

“If you’re a blue state governor, why would you want taxpayers in your state sending their money to some other state?” he asked. “I think that’s a political liability.”

Despite Democrats’ longstanding opposition to vouchers for private school and education savings accounts, which can be used for homeschooling, some, like North Carolina Gov. Josh Stein, say the program is a chance for more public school students to receive tutoring and afterschool programs..

That’s what the Afterschool Alliance emphasized in its submission. The advocacy organization suggested that perhaps some scholarship programs could focus on students who need afterschool activities while others could stick to granting private school scholarships.

According to a December Echelon Insights poll, conducted for the National Parents Union, more than three-fourths of parents support the tax credit if it’s targeted only to public school students for tutoring, summer learning and afterschool programs. But that figure drops to 40% if the benefit is restricted to private school tuition.

In the spirit of “returning education to the states,” the advocacy group, in its comment, wrote that states should be able to design and run the programs in a way that reflects “their unique policy landscapes, community needs and family priorities.”

The organization also wants the Treasury Department to allow states to evaluate schools and providers “to assess whether the programs participating are delivering meaningful, measurable results.” Such data, including average scholarship amounts and the demographics of students served, should be publicly available, the comment said.

Roger Severino, vice president of domestic policy at the conservative Heritage Foundation, told The 74 that he’s not opposed to public school students receiving scholarships for tutoring or afterschool enrichment, but he doesn’t want the program to become “a backdoor diversion of funds to public schools themselves.”

To religious groups, one chief concern is that states might attempt to require private schools to change their admission policies. In its comment, the Christian Legal Society, an organization of Christian attorneys, referenced litigation in Maine, where religious schools are suing over a requirement that they accept all students, regardless of religion, disability, sexual orientation or gender identity, if they want to participate in a private school choice program.

“It is important that federal regulations prevent governors from yielding to the temptation to play politics with the program by adding additional regulations to distort it,” the group’s comment said. “Such regulations,” they wrote, would lead to “inevitable lawsuits” and limit options for families.

Microschool founders and advocates have additional concerns. A section of the tax credit law says that a K-12 “school” is whatever a state law defines it to be. The problem is that most states don’t legally recognize microschools even though they represent a fast-growing sector within the private school landscape. A Tulane University study published last year showed that most schools participating in state school choice programs enroll around 30 students — the size of many microschools.

“Families turn to programs like ours because their children’s needs cannot be met in traditional settings,” Alexandra Batista. the owner of Steps Learning Center in Orlando, Florida, wrote in a comment to the Treasury Department. “Excluding these types of learning environments due to narrow or outdated definitions would further disadvantage students who already face significant barriers.”

Some organizations, like the left-leaning Center for American Progress, want the federal government to adopt an official definition of microschools as a way to better track them and monitor the quality of education they provide.

But those in the movement are “not excited about that prospect,” said Don Soifer, CEO of the National Microschooling Center. Some microschools in states with education savings accounts operate like small private schools, while others are more like homeschool co-ops. Some are required to earn accreditation in order to receive state funds; others aren’t.

In his comment to the Treasury Department, Soifer said that it would be “highly inappropriate and contrary to legislative intent” for officials to adopt an official definition of a microschool when “the industry itself has no consensus.”

Schilling, the lobbyist, said he hopes the Treasury Department addresses the issue in the rules.

“Microschools feel like they ought to be able to participate in this and we completely agree,” he said. “The intent of the legislation was for a student, in any educational environment, to benefit.”

What's Your Reaction?