AI Trailblazer Google Doesn’t Want Schools to ‘Bypass the Human’

In 1999, the Indian computer scientist and educational theorist Sugata Mitra created a small, if audacious, learning experiment: He and colleagues at the National Institute of Information Technology cut a hole in a street-level wall of their New Delhi office building and mounted an Internet-connected personal computer, usable by anyone who passed by. No instructions, […]

In 1999, the Indian computer scientist and educational theorist Sugata Mitra created a small, if audacious, learning experiment: He and colleagues at the National Institute of Information Technology cut a hole in a street-level wall of their New Delhi office building and mounted an Internet-connected personal computer, usable by anyone who passed by. No instructions, no suggestions, no lesson plans. Just access.

Within hours, Mitra would later write, children from a nearby slum appeared “and glued themselves to the computer.” They learned how to use the mouse, download games and music, play videos and surf the Web, all by teaching themselves.

The experiment in what Mitra called “minimally invasive education” was replicated worldwide. It became hugely influential in the ed tech world, evidence that children simply need access to tools to be successful.

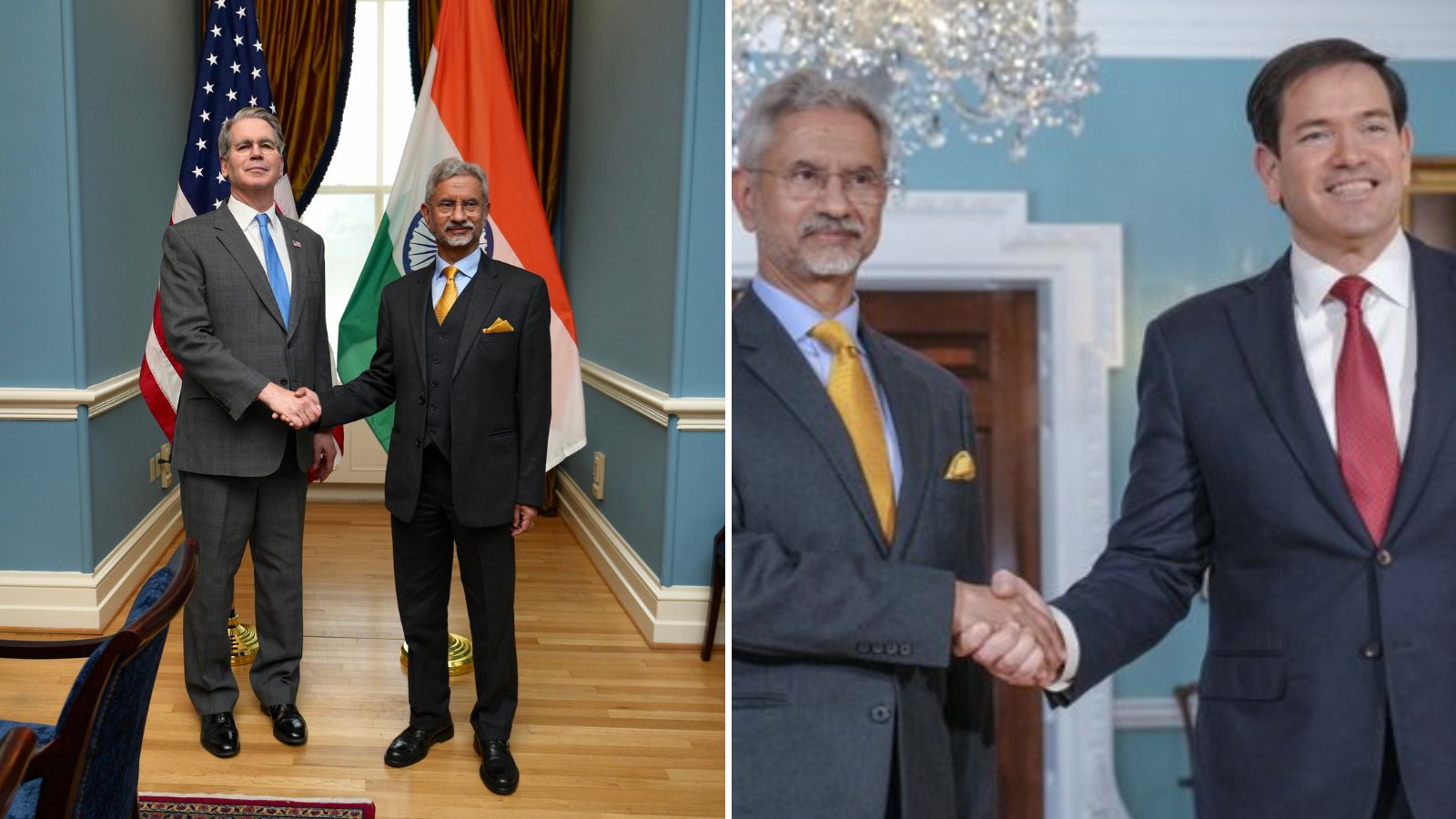

But don’t mention Mitra too enthusiastically to Ben Gomes, the computer scientist who co-leads Google’s education efforts. While the “hole in the wall” experiment is a hopeful, charming story, he’d say, it’s missing a key element: teachers.

People are fundamental in the learning process. People learn from other people, and people learn because of other people.Ben Gomes, Google

“We are paying attention to pedagogy, and we’re working with the teachers,” he said. “We’re not saying we just want a thousand flowers to bloom randomly.”

As AI becomes more ubiquitous in schools, Gomes maintains that Google has a duty to train teachers not just how to use its products but also how to help them move students from taking shortcuts to using AI for deeper, often independent learning.

That strategy could dull longstanding complaints that ed tech more broadly is focused on replacing teachers with tech tools that don’t measure up.

“It’s a belief backed by science, to a large extent, that people are fundamental in the learning process,” Gomes said, “that people learn from other people, and people learn because of other people.”

Children certainly can and do learn independently, but deep conceptual understanding and literacy require guidance — especially now, nearly three decades after Mitra’s hole in the wall, with many developers looking for ways to replace teachers with AI.

“Teachers are critical in this process,” Gomes said. “We don’t want to bypass the human.”

AI as ‘thought partner’

In a recent white paper, Gomes and a handful of colleagues explored how AI could reverse declining global learning, largely through supporting teachers and turbocharging personalization. In mid-January, Google said it was doubling down on AI in the classroom, offering its AI-driven Gemini app to more educators and students for free, making tools such as full-length practice SATs available and partnering with Khan Academy to power a writing coach tool.

The search giant has put a former NASA trainer in charge of much of the effort. Julia Wilkowski, a neuroscientist, has also taught sixth-grade math and science. She began her career at an outdoor environmental school, where she recalled hiking trips in which she’d ask students to figure out the velocity of a stream using only an orange, a length of string and a stopwatch.

Wilkowski now spends “pretty much 100% of my time” focused on ensuring that Google’s AI for students rests on sound learning science.

In interviews over the past few weeks, Gomes and Wilkowski spoke openly about their work, in several instances admitting that much of it amounts to helping teachers find ways to get students to stop outsourcing their thinking.

“Teachers have the opportunity to teach their students how to use these tools ethically and effectively that don’t bypass those critical thinking skills,” said Wilkowski.

As an example, she said, she has worked with English teachers to help them instruct students on how to use AI as “a thought partner” in essay writing, not as the writer itself.

These teachers, she said, have succeeded by breaking down essay writing into its component parts and openly discussing its goals. They use AI to help students brainstorm essay topics, refine thesis statements, help generate first drafts and offer feedback on them, giving students “guidance and guardrails” without allowing them to turn in AI-written essays.

The work, stretching back a year and a half, “has really informed my optimism about how AI can be used successfully,” she said.

Guided learning

Both Wilkowski and Gomes spoke often of “guided learning,” saying students learn best when they move beyond simple answers to develop their own ideas and think critically. To get them to do so, teachers must guide them with carefully designed questions.

There's no published research showing that GenAI chatbots have the pedagogical content knowledge to be effective Socratic tutors.Amanda Bickerstaff, AI for Education

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Google has an app for that, a section of Gemini that acts much as a private tutor or guide, offering students a taste of “productive struggle” that engages but also challenges them without offering answers (at least not immediately). Rather, it steers them to the answer through a series of questions.

Gomes said the principle is working its way into most of Google’s AI products, including a newer one called Learn Your Way, which uses the technology to help students learn topics in interactive, more appealing ways most textbooks can’t: as a text with quizzes, a narrated slideshow, an audio lesson and a “mind map” that lays out related ideas in connected graphics.

At its root, Gomes said, the dilemma over AI and cheating stems from motivation. “If I look back at my own childhood, there are certainly cases where I was just interested in getting something done for tomorrow,” he said. “And there are other cases where I was curious and I wanted to read more.”

The ratio between how much time students spend in one state vs. the other varies, he said, “but getting more people into the state where they are motivated, I think, is the goal.”

But Amanda Bickerstaff, co-founder and CEO of AI for Education, a training and policy organization, said the reasons students turn to AI are “far more complicated than lack of motivation.”

Students are dealing with “perfectionism, high-stakes assessments that prioritize grades, skill and language gaps,” among other dilemmas. “Framing this primarily as a motivation issue oversimplifies what’s actually happening in classrooms.”

She said Google’s shift toward Socratic reasoning “sounds promising, but there’s a fundamental problem: There’s no published research showing that GenAI chatbots have the pedagogical content knowledge to be effective Socratic tutors.”

The chatbots are “sycophantic by nature,” Bickerstaff said, offering answers and completing tasks even when not explicitly asked to. “That’s the opposite of productive struggle.”

And most young people, she said, don’t have sufficient AI literacy to use these tools strategically. “Without that foundation, chatbots become an “easy” button for schoolwork rather than a learning tool. You can’t solve that problem through interface design alone.”

More, better feedback

For her part, Wilkowski said much of the struggle over AI comes down to feedback: How much should students get, how often, and what should it look like?

Wilkowski said her daughter is in high school and was required to write an essay for a final exam in December. When Wilkowski spoke to The 74 in early January, she said the essay still hadn’t been graded.

“I would rather have AI-generated feedback,” she said. “Give the first draft, and then the teacher [can] review it, of course, before giving it to the students.”

Teachers have the opportunity to teach their students how to use these tools ethically and effectively that don't bypass those critical thinking skills.Julia Wilkowski, Google

More broadly, she said, AI could soon change how students are assessed altogether, helping teachers move away from tools such as multiple-choice tests, whose problems are well-known in the testing world: They’re easy to create, administer and grade, and they’re reliable. But they also allow students to guess rather than show understanding, and they encourage students to learn by rote memorization rather than deeper engagement with material.

Multiple-choice tests also can’t evaluate higher-order thinking skills, creativity, student writing or the ability to construct arguments. If AI can make essays or long-form questions or even projects easier to grade, wouldn’t that put the multiple-choice test out of business?

“Let’s say you’re in physics class and you’re studying acceleration-versus-time graphs and you ride your bike home,” Wilkowski said. “An AI tool might pop up and say, ‘Hey, here’s your acceleration-versus-time graph of your bike ride home. What did you notice about your velocity? How did it change as you changed acceleration? Was there a hill that you had to overcome?’”

More relevant assignments and assessments, she said, could get students to think more critically, incorporating school into their real life in deeper ways. “It goes back to the heart of what excited me as a teacher: those excited, hands-on lessons. I’m seeing a way that … AI can facilitate those in the future.”

AI for Education’s Bickerstaff said it’s encouraging to see Google working to create more “fit-for-purpose tools” for student use.

“The education sector desperately needs companies to move beyond general-purpose chatbots and build tools that actually support cognitive work rather than replace it,” she said. “But there’s still a lot of work to do — and a lot of research that needs to happen — before we can know if these tools are effective learning guides.”

What's Your Reaction?