How Dubai's vanished landmarks still live on in directions

The Trade Centre Roundabout is being reconfigured. As part of a broader redevelopment, the Roads and Transport Authority (RTA) is converting the existing roundabout into a surface intersection, a move aimed at easing congestion at one of Dubai's busiest junctions.Some of that change is already visible. Two bridges opened last month, cutting travel time between 2nd December Street, Sheikh Rashid Road and Al Majlis Street. Even as the road layout changes, many still refer to the junction as Defence Roundabout.This is not new. Over the decades, Dubai's road network has been repeatedly altered. Junctions have been rebuilt, renamed, or absorbed into larger interchanges. What has proved more durable are the reference names people continue to use in everyday speech.Stay up to date with the latest news. Follow KT on WhatsApp Channels.Before GPS screens and Makani codes, residents relied on landmarks: the clock, the cinema, the roundabout with the statue. Many of those names continue to be used long after the structures themselves are gone.“People came and went all the time,” says Emirati cultural consultant Mohammad Kazim. “So landmarks mattered. They were how you explained the city to someone who didn’t know it yet.”Sheikh Zayed Road did not begin as a skyline. In the early 1970s, it was Defence Road, a stretch of asphalt running through open land. As traffic grew and the city pushed outward, a roundabout took shape along it, becoming a convenient point of reference.The junction was later rebuilt and renamed Trade Centre Roundabout. The layout changed but the older name didn’t."It’s passed down,” says a taxi driver who has worked Dubai’s roads for two decades. “From driver to driver.”The pattern repeats across the city. Vanished landmarks continue to function as verbal signposts, even as navigation itself has become largely digital. One such reference point no longer exists at all.Strand Cinema, a popular Bur Dubai theatre demolished in the 1990s, still surfaces in everyday directions.In Deira, drivers still say ‘Clock Roundabout’ when pointing someone towards the old souks or Creek crossings, even though traffic lights replaced the circle years ago. Near Garhoud, Falcon Roundabout survives as a phrase long after the sculpture was moved to a park in Mirdif.Other cues ranged from cinemas and supermarkets to police stations and schools. People were ‘near Picnic Home’ in Satwa or “near the American School” in Jumeirah, long before road numbers or signage arrived.Longtime British expat Josephine Finzi remembers how directions once worked. “In the days before Makani codes and satnavs, we got around by visual clues,” she says. “‘Past Spinneys on the beach road and left at the zoo’ or ‘right at the clock tower, left at the eternal flame roundabout.’”Some of those landmarks have disappeared. Others survive only as names, detached from their original form.“The Defence Roundabout made sense at the time,” Finzi adds. “Now it’s an interchange, but the name still tells you where you are.”For many early residents, the city once ended abruptly.“Golden Sands and Silver Sands were just two pretty buildings surrounded by sand,” recalls Peter Halliday, who arrived in Dubai in 1982. “If you got lost, you always had the Trade Centre on the horizon. You could see it from tens of kilometres away.” Beyond that, the cues were unmistakable. “If you went past Galadari Roundabout and saw Al Mulla Plaza, you knew you were heading towards the border post and the wilds of Sharjah,” Halliday says.British expat Len Chapman, 88, who arrived in 1971, traces these habits further back.“UK architect John Harris introduced roundabouts to Dubai in his 1959 town plan,” he says. “They became the city’s punctuation marks.”Some acquired nicknames that stuck. "The Flour Mills roundabout became the Falcon or less flatteringly, the Budgie,” Chapman says. “It sat next to grain silos, which attracted thousands of pigeons.”The falcon has long since flown. The name hasn’t.Chapman points to other roundabouts that once structured daily movement. The Flame Roundabout, first called the Eternal Flame, was a major landmark before it was moved and later installed as a monument in Al Khabaisi Park.Wildlife expert Dr Reza Khan, who retired from Dubai Municipality in 2024, recalls how even animals became points of reference.“At the zoo in Jumeirah, the giraffe’s long neck was visible from outside,” he says. “People would say, ‘Turn left 200 metres from the giraffe’s neck.'"Along Al Wasl Road, Emirati resident Rany Doleh remembers how his family’s Chinese-pagoda-style villa once served as a navigational marker, not just for drivers, but even for ships offshore.Commercial spaces played a similar role.In Bur Dubai and Karama, drivers still refer to ‘Sana Signal’ named after a clothing store that closed in 2018. Ask for it today and most veteran drivers know where to slow down, though newer residents are often left with questions.Online, many of these older reference points co

The Trade Centre Roundabout is being reconfigured. As part of a broader redevelopment, the Roads and Transport Authority (RTA) is converting the existing roundabout into a surface intersection, a move aimed at easing congestion at one of Dubai's busiest junctions.

Some of that change is already visible. Two bridges opened last month, cutting travel time between 2nd December Street, Sheikh Rashid Road and Al Majlis Street.

Even as the road layout changes, many still refer to the junction as Defence Roundabout.

This is not new. Over the decades, Dubai's road network has been repeatedly altered. Junctions have been rebuilt, renamed, or absorbed into larger interchanges. What has proved more durable are the reference names people continue to use in everyday speech.

Stay up to date with the latest news. Follow KT on WhatsApp Channels.

Before GPS screens and Makani codes, residents relied on landmarks: the clock, the cinema, the roundabout with the statue. Many of those names continue to be used long after the structures themselves are gone.

“People came and went all the time,” says Emirati cultural consultant Mohammad Kazim. “So landmarks mattered. They were how you explained the city to someone who didn’t know it yet.”

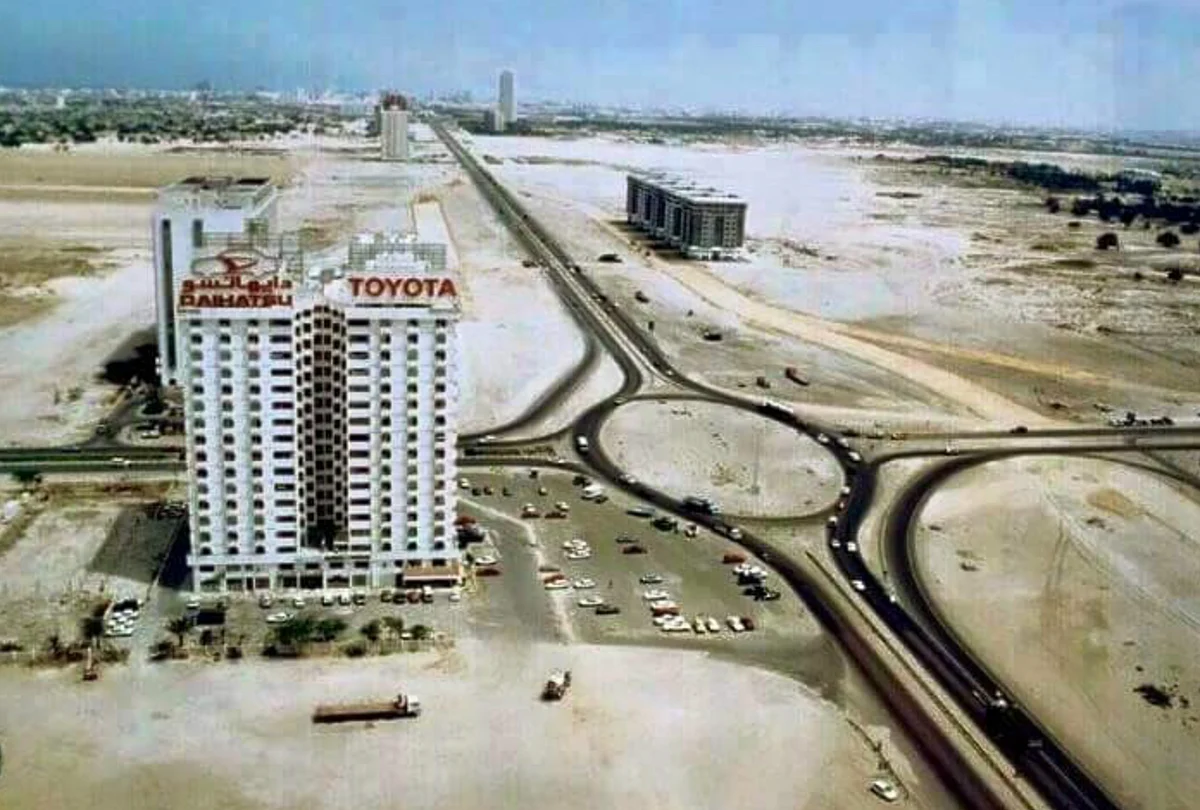

Sheikh Zayed Road did not begin as a skyline. In the early 1970s, it was Defence Road, a stretch of asphalt running through open land. As traffic grew and the city pushed outward, a roundabout took shape along it, becoming a convenient point of reference.

The junction was later rebuilt and renamed Trade Centre Roundabout. The layout changed but the older name didn’t.

"It’s passed down,” says a taxi driver who has worked Dubai’s roads for two decades. “From driver to driver.”

The pattern repeats across the city. Vanished landmarks continue to function as verbal signposts, even as navigation itself has become largely digital. One such reference point no longer exists at all.

Strand Cinema, a popular Bur Dubai theatre demolished in the 1990s, still surfaces in everyday directions.

In Deira, drivers still say ‘Clock Roundabout’ when pointing someone towards the old souks or Creek crossings, even though traffic lights replaced the circle years ago.

Near Garhoud, Falcon Roundabout survives as a phrase long after the sculpture was moved to a park in Mirdif.

Other cues ranged from cinemas and supermarkets to police stations and schools. People were ‘near Picnic Home’ in Satwa or “near the American School” in Jumeirah, long before road numbers or signage arrived.

Longtime British expat Josephine Finzi remembers how directions once worked. “In the days before Makani codes and satnavs, we got around by visual clues,” she says. “‘Past Spinneys on the beach road and left at the zoo’ or ‘right at the clock tower, left at the eternal flame roundabout.’”

Some of those landmarks have disappeared. Others survive only as names, detached from their original form.

“The Defence Roundabout made sense at the time,” Finzi adds. “Now it’s an interchange, but the name still tells you where you are.”

For many early residents, the city once ended abruptly.

“Golden Sands and Silver Sands were just two pretty buildings surrounded by sand,” recalls Peter Halliday, who arrived in Dubai in 1982. “If you got lost, you always had the Trade Centre on the horizon. You could see it from tens of kilometres away.” Beyond that, the cues were unmistakable. “If you went past Galadari Roundabout and saw Al Mulla Plaza, you knew you were heading towards the border post and the wilds of Sharjah,” Halliday says.

British expat Len Chapman, 88, who arrived in 1971, traces these habits further back.

“UK architect John Harris introduced roundabouts to Dubai in his 1959 town plan,” he says. “They became the city’s punctuation marks.”

Some acquired nicknames that stuck. "The Flour Mills roundabout became the Falcon or less flatteringly, the Budgie,” Chapman says. “It sat next to grain silos, which attracted thousands of pigeons.”

The falcon has long since flown. The name hasn’t.

Chapman points to other roundabouts that once structured daily movement. The Flame Roundabout, first called the Eternal Flame, was a major landmark before it was moved and later installed as a monument in Al Khabaisi Park.

Wildlife expert Dr Reza Khan, who retired from Dubai Municipality in 2024, recalls how even animals became points of reference.

“At the zoo in Jumeirah, the giraffe’s long neck was visible from outside,” he says. “People would say, ‘Turn left 200 metres from the giraffe’s neck.'"

Along Al Wasl Road, Emirati resident Rany Doleh remembers how his family’s Chinese-pagoda-style villa once served as a navigational marker, not just for drivers, but even for ships offshore.

Commercial spaces played a similar role.

In Bur Dubai and Karama, drivers still refer to ‘Sana Signal’ named after a clothing store that closed in 2018. Ask for it today and most veteran drivers know where to slow down, though newer residents are often left with questions.

Online, many of these older reference points continue to surface in everyday exchanges. Facebook groups such as Dubai — The Good Old Days regularly share photographs of demolished buildings and debate timelines, adding personal context to the city’s changing landscape.

What's Your Reaction?